A Review of Greg Schutz’s Joyriders

There’s a moment near the beginning of “Ten Thousand Years,” the sixth story in Greg Schutz’s debut short story collection, Joyriders, where the sober protagonist Carter drinks cream soda on his back stoop as he watches “combines drag the fields, corn crackling in their combs.” The fields will return in a horrific moment at the end of the story, but for now Carter sinks into reluctant gratitude for the simplicity and stability of his present life as the reader settles into a story with the sounds of the corn harvest reverberating in their ears.

Schutz writes settings with the honest heart of an author who has lived them. The collection traverses the Michigan and Wisconsin shores of the Great Lakes as well as the Appalachian Mountains west of Asheville, North Carolina. We find ourselves on quiet backroads, in narrow house trailers, desolate late-night gas station parking lots, and the occasional quaint lakeside rental cottage. Schutz is a writer who revels in language. There are “sodium lamps suspended like fuzzy tangerines,” the “wet, bright tunnel” of driving with high beams at night; there’s the rural veterinarian who “eases the red folds” of a Holstein’s uterus back into her body after she births a calf. Language and narrative are held in equal tension. The sentences rise exquisitely off the page, the effect similar to the experience one has after reading Annie Proulx’s work: the conviction that certain writers can perform miracles.

In Joyriders, liminal spaces are the ones where characters’ lives most often crack open. Big things occur elsewhere in the collection, but it’s these inescapable spaces—empty roads, doorways, pickup truck cabs—that twist the characters backwards into the labyrinthine of the past. For example, in “Ten Thousand Years,” the narrative shifts between time and memory create three layers of family trauma: one with Carter, one with his short-term girlfriend, Claudia, and one with a young pregnant girl who Carter happens to see during a routine heating and plumbing job. Although the story itself is told singularly from Carter’s perspective, the reader is given a glimpse into the ways trauma ripples throughout a person’s life.

In “The Little Flashes,” published in Story, Issue 19, the unnamed female narrator enters into an affair with Thom. She’s a lawyer; he’s a carpenter, married and with a daughter. The narrator knows from the beginning the affair is a terrible idea, yet she justifies her desire by reframing it as need—she’s lonely and newly understands her loneliness as having begun in childhood. In the structurally straightforward “You Are the Greatest Lake,” the narrator returns, this time vacationing with Thom and his daughter at a cabin on the Saginaw Bay in Michigan. The story’s penultimate paragraph both collapses and elongates time. This moving sequence reveals the impossibility of a lasting relationship between three characters by not only capturing the beauty of what their connection might have been but also infusing the narrator’s childhood with new understanding. And in the novella-length “Breeder’s Cup,” the intersplicing timelines and points of view hint at possibilities for love after grief and heartbreak, with the story ending on a moment of both mercy and grace.

The mostly working-class and rural characters who populate Joyriders remain indivisible from their surroundings—a major strength of this short story collection and a testament to Schutz’s skill for writing both place and people. A handful of characters reappear across stories, their presence shifting with each narrative perspective, each leap in time. For instance, the rural veterinarian Doc, along with his daughter, Dani. Doc’s tender relationship to animals is a moving addition in a collection where distance and loneliness shape the characters’ lives. Joyriders is laden with other doubles as well—people and moments that echo through a character’s life, informing their choices and, occasionally, their regrets.

In the hands of a lesser writer, the darkness and pain pervading this collection might sit too heavily in the heart. And while several stories burrow achingly into one’s chest, Schutz never leaves the reader without hope—even if it’s the type of hope we know comes with eventual devastation. Even the brief, final story, “Not for Nothing,” where a man is nearly crushed to death by a felled tree, ends with bewildered, yet joyful, laughter. Joyriders is a brilliant and audacious collection that is both gut-wrenching and buoyant.

A Conversation with Greg Schutz

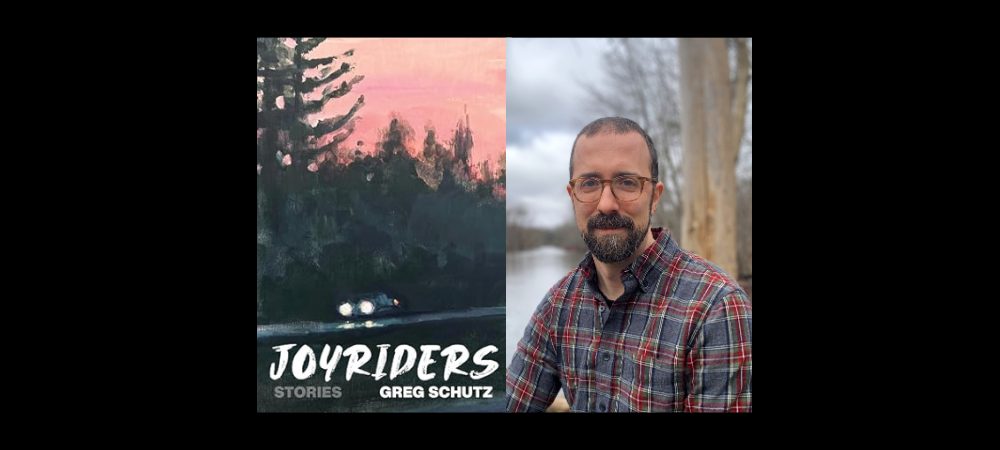

Greg Schutz is the author of Joyriders (University of Massachusetts Press, 2025). Stories from Joyriders have appeared in numerous literary journals, including Story, Ploughshares, American Short Fiction, Alaska Quarterly Review, and the Colorado Review. They’ve been nominated for three Pushcart Prizes, anthologized in New Stories from the Midwest and listed among the distinguished stories of the year by both Best American Short Stories and Best American Mystery Stories. Greg can be found online at www.gregschutz.com.

Fiction Editor Lacey N. Dunham and Greg Schutz corresponded with one another via email to discuss the craft and inspiration behind the stories included in Joyriders.

INTERVIEWER

Each night I read your book with an ache in my chest because you never shy away from placing your characters into difficult situations. At the same time, your prose made me yearn to do better as a writer. I assume the sentence-level line edits come later in the process (though let me know if I’m wrong, and I’ll find a pillow to sob into!), so can you start by telling us what comes first for you when you construct a story: character or plot?

GREG SCHUTZ

At this point, having worked steadily and exclusively on short stories for half my life, I probably discover most of my new stories in older stories—in the false starts, wrong turns, and dead ends of stories completed or abandoned. A diagram for this might resemble a phylogenetic tree: a relatively small set of common ancestors, early stories, evolving through trial and error into a diversity of new narratives, with each producing, through its own failures and fragments, new unforeseeable offspring.

Certain fragments stick with me: characters, concepts, scenes, images, sentences. The stories where they originated may end up not needing them or may be abandoned altogether, but the fragments live on in my memory, in my notebooks, or on my hard drive. Their hold suggests some subconscious significance for me. Eventually, I’ll return. I’ll try writing my way toward an old fragment or launching from it.

But, for me, each new story tends to accrete on the level of language, which is to say I explore and discover one sentence at a time. There’s a feeling I’m trying to stay in touch with—a sort of wordless apperception of the story’s core emotions, if that makes sense—through language. Each sentence prompts the next, both in terms of content, obviously, but just as importantly in terms of rhythm and sound.

I write slowly. I need to feel generally satisfied with one sentence before moving on to the next. But that satisfaction is no guarantee against mistakes. I’ll often discover I’ve lost the thread, lost touch with the emotions I’m seeking, and I’ll have to backtrack to figure out where and how that happened.

Many of the stories in Joyriders took multiple years to complete. But once I do have a finished draft, there’s usually relatively little line editing to be done.

I’ve tried writing the more commonly prescribed way—quickly establishing the story’s shape, discovering its plot, and worrying about language later—but it doesn’t feel as natural. My connection to the material is mediated by language, rather than some larger storytelling sense of plot. Moreover, working quickly just isn’t fun for me. I love sitting closely with a sentence, trying out various permutations, testing how each possibility makes me feel, how each reveals something slightly different about the characters or suggests a slightly different narrative path. Why deprive myself of that slow, playful labor?

INTERVIEWER

All of your characters—including the teenage girls—are written with such confident authenticity. I call out the teenage girls specifically because I personally struggle with how writers often portray young women in narratives, and yet you never seem to stumble. What’s your trick for slipping in a variety of characters?

SCHUTZ

My guess is that if I’d approached writing from perspectives significantly different from my own as a trick—in other words, as something to be accomplished through consciously applied craft techniques—I may not have attempted it. I may not have felt I had the right to do so.

But I don’t see this as primarily a matter of conscious craft. The characters in our fiction are like the characters in our dreams: no matter who they appear to be, each is actually us—some aspect of ourselves, masked. (I regularly have dreams in which I’m not myself, nor anyone remotely similar to myself. Is this a fiction-writer thing?) Trying on that mask—portraying that character, in a dream or fiction—is an attempt to access something in the subconscious, some deep well of meaning and emotion. If the emotions produced by working with this character feel authentic, if my language can be elevated to the task, if my approach to this character and her life can be made with the same wide-open heart I might need to bring to a therapy session, then I’ll trust myself to proceed.

Again, we’re back to sentences and the feelings they generate. In working with any character, whether superficially similar to me or not, I’m trying out words and rhythms, seeking combinations that reproduce the feeling that thinking about this character generates for me. (I’d be hard-pressed to verbally describe any real-life friend of mine in a way that feels both accurate and complete, but because I know them well, each generates a distinct complex feeling. That’s what I’m searching for with my characters.) If I take the time to explore this character through my sentences, growing increasingly vivid, complex, and consistent on the level of language, then I can ultimately trust (or at least hope!) that an authentic-feeling imagined human will arise as an emergent property of the language.

INTERVIEWER

I’m struck by the instances of doublings that occur throughout your collection: characters appear in multiple stories, situations uncannily seem to repeat in people’s lives, settings double and redouble. Why do you find yourself returning to certain characters and settings more than once? For your characters, who are often trapped by their pasts, what narrative role can doublings or repeated instances (real or imagined) have in their story arc?

SCHUTZ

Doublings: I wasn’t necessarily conscious of this before, but it immediately strikes me as true. You’ve reminded me that among the many fragments to which I keep returning are not one but two stories that feature brief encounters with literal doppelgängers! So doublings, in various forms, are clearly on my mind.

Two different sets of characters recur within Joyriders. There’s Doc, a veterinarian, recently bereaved, along with his teenage daughter, various family friends, his colleagues, and clients—the community around him as he navigates his grief. And in another pair of stories, there’s a young lawyer who embarks on an affair, only to fall in love, in a sense, with her lover’s young daughter in a way that begins to raise questions about her own childhood.

With neither character did I write a first story intending to write more. But these characters kept coming back to me. I kept daydreaming about them, imagining their lives. I must not have been done processing whatever subconscious structures they connected me to. In the case of the young lawyer, I suspect her return had something to do with the way my life—though not through an affair!—unexpectedly enriched me with a stepdaughter.

Ultimately, if I’m writing as a means of narratively processing subconscious emotions and impulses—a concept I first encountered in Patricia Hampl’s wonderful essay “Memory and Imagination,” and which immediately struck me as true—then some degree of doubling or recurrence is inevitable. I am who I am, for better or worse. These recurrences suggest stable aspects of my personality, stable concerns. Similarly, my characters are who they are, and though their actions may change their lives, their selves remain inescapable. We can only change ourselves so much! This is why, for many of these characters, part of the challenge is how to live with themselves as themselves—how to understand, forgive, and love themselves.

We’re only trapped by our past if such forgiveness remains beyond us.

INTERVIEWER

Forgiveness is a recurring theme in your collection. You write of characters who cannot forgive themselves for past mistakes, of characters who cannot be forgiven, and of characters who cannot seem to forgive others. You also write compellingly of forgiveness’s cousin, mercy, particularly in the character of Doc, who was my favorite. What draws you to these monumental themes? What is your own relationship with forgiveness and mercy?

SCHUTZ

I love your description of mercy as forgiveness’s cousin! It suggests these values are both related and distinct: mercy as the practical manifestation of forgiveness, perhaps, the way in which forgiveness finds embodiment through action. (Without forgiveness, mercy is merely forbearance.) I wonder if this distinction can be mapped onto familiar craft terminology: the challenge of forgiveness as the crux of internal conflict, say, and the enactment of mercy as the climax of external conflict. This would be a meaningful alternative to the confrontational language we usually use to discuss conflict!

On the one hand, these themes are monumental, as you’ve said. After all, if what I mentioned above about being trapped by our past has any truth to it, then forgiveness and mercy must be at the heart of what it means to feel authentically at home with our authentic selves in this world and also at the heart of what it means to offer someone else the opportunity to feel the same. But on the other hand, these are also very humble values, at risk of invisibility in a screen-mediated age. They don’t drive clicks. They aren’t particularly meme-worthy, performative, or profitable. Maybe that’s why I’m drawn to them in my stories—because they’re monumental, and because they’re small.

This brings us back to conflict. A story that contemplates forgiveness and mercy is unlikely to feature many explosions. It’s likely to be about the slaking of a thirst rather than the lighting of a fuse. Yet at the same time, forgiveness and mercy are tremendously challenging values to actually live by, aren’t they? What I was keen to find—and what writing from Doc’s point of view in particular helped me learn—was a way of rendering characters’ interiority, their inner lives, which would be dense, clear, and rich enough to give that challenge real dramatic weight.

INTERVIEWER

As I mentioned, the rural veterinarian Doc was a favorite character of mine, I think partially because of his tenderness and care for animals, both domestic and wild. What’s your relationship to the natural world, especially the most vulnerable creatures and non-human animals in it?

SCHUTZ

We could add tenderness and care to our list of humble yet monumental values, couldn’t we? Like mercy, they’re the practical embodiments of some particular inward stance. In this case, the inward stance might be love.

Like most veterinarians I’ve met—including and beginning with my father—Doc loves animals. His love for them is deep and abiding, and one of the great pleasures of writing from his perspective was discovering the various ways in which his love for the animals around him feeds and sustains him across several extremely difficult years in his life. In his grief, he cares for himself by caring for them, although I don’t think he’s ever quite aware that’s what he’s doing.

This may be one of the quiet themes in Joyriders: the way attention offered to the natural world rebounds and enriches characters’ lives, though not typically in ways they might intend. For many characters—I’m thinking, for instance, of that young lawyer watching her lover’s daughter dip a baited hook in Lake Huron for bluegills, witnessing that little girl’s un-self-conscious devotion, and then attempting it herself—this act quietly reframes their sense of their own situations, their own selves, revealing possibilities unapparent before.

Because my father was a veterinarian in rural Wisconsin, I spent a lot of my childhood wandering around farms, around animals, and also just enjoying the outdoors: camping, hiking, fishing, snorkeling, birdwatching. I was fortunate to be trained in quiet, outward-facing attention from an early age, and it remains as essential as my writing practice to my life as a whole. I’m glad this shines through in my fiction.

INTERVIEWER

Your rural settings are written with a specificity that grants your characters grace. I grew up on a farm in rural Michigan, where some of your stories take place (I’ve been to the beach in Caseville), and I lived for a number of years in rural Appalachia (though in Virginia, not North Carolina, as you write about), and I admit to feeling seen in a way I don’t often experience in fiction. Can you talk about the choice to place your stories in non-urban, non-coastal, and (dare I say it?) non-elite settings? Have you ever tried to write a New York City story?

SCHUTZ

I grew up in central Wisconsin until I was twelve, when my family moved to western North Carolina. After attending college in New Orleans, I came here to Michigan, where I’ve lived ever since. So the stories in Joyriders are almost exclusively set in the places I’ve called home, places I’ve come to feel shaped by.

I’ve visited New York City several times, but could I set a story there? Frankly, I don’t think so—or, more precisely, I doubt I could set a story there that really mattered to me. Because I can’t write about that place with a native intimacy, it would almost have to be, at least in part, a story about displacement—country mouse in the city, Nick Carraway in East Egg, or other well-worn narrative paths—when what I’m more interested in as a writer is a particular kind of emplacement.

The characters in Joyriders have all been shaken from their daylight lives—by grief, by heartbreak, by love and longing, by marriage and parenthood, by addiction and the ongoing work of recovery—but find, once loosed from their old selves, a freedom to be exercised for good or ill, a renewed sense, often frightening or even dangerous, of the open destiny to which the collection’s title alludes. This freedom is almost always rooted in place, in the ways each character’s attention to setting, sharpened by crisis, unveils new opportunities, new ways of living where they are.

INTERVIEWER

Your collection includes pieces under 2,000 words and a piece that runs 14,000 words—an astonishing range for a writer in a single book! I’m curious how you approach writing stories of vastly different lengths. For example, do you know when you set out that you’re writing flash fiction versus something veering into novella territory? Does your process vary depending on the length of the piece?

SCHUTZ

I tend to know from the outset whether a piece is going to be a microfiction, a flash fiction, or a short story, perhaps because each form makes different demands at the sentence level, which is where I discover a narrative. The shorter the piece, the greater the demand for poetic compression within each sentence, the greater the size of the average leap, gap, or shift between sentences, and the more that must be accomplished through subtext and implication.

So the feel I have for the work I’m doing in any given writing session, down in the moil of individual sentences as they come together, is necessarily modulated by my expectations for the piece—its final form, its length. Or else the insight arrives in reverse, and I’ll recognize, from something about the sentences I’m producing, what the thing I’m working on wants to be.

I’ve been wrong before, but only in one direction. I’ve never had something I thought was a micro or a flash grow into a longer story, but I’ve sometimes discovered, within a larger mass of material that just isn’t coming together, a core of something meant for a more concentrated form. “A High School Production of Titus Andronicus” was like that. I spent a decade, off and on, exploring a few months in the life of a troubled young woman who happened to have a minor part in that play. I was interested in her fraught home and social life, the fraught moment in American history at which the story was set, and her feelings as an adult looking back, only to finally realize “the play’s the thing.” The more I tightened the narrative frame, the sharper the story became. Soon I had a piece of flash fiction I loved, as well as a great mass of fodder—dozens of single-spaced pages, perhaps a hundred—that will feed new stories long into the future.

INTERVIEWER

Your collection took more than a decade to come to fruition. What writing and publishing advice do you have for writers who might want to release a short story collection?

SCHUTZ

Never forget why you love the short story: its fiery compression, its sudden fevers and chills, its sonata-like weave of pattern and contrast, its limber gymnastic muscularity, its mysterious obliqueness. A love for the form, and for your endless imperfect practice of it, may be the best sustenance. Remember, stories are not mere circuit training for a novel. They are their own entity, their own way of processing lived experience. Reading and writing them daily, living with them, is a solitary inward discipline in a way that, for me at least, the novel—more outward-facing, more social, a public form, more at ease in the marketplace, and more readily commodified—could never be.

But perhaps the length of time it took me to see this collection into the world makes me less qualified to render advice on the subject! I’m better off just speaking for myself, describing my own experience.

As I’m sure is obvious by now, little about my writing process is neat or efficient. It’s all slow, sentence-by-sentence probing, with lots of wrong turns along the way. I couldn’t write like this, which is the only way I know how to write—or at least the only way to write that I actually enjoy—if I always had one eye on the outcome, on the idea of a published book or even just a finished story. In order to follow the trail my sentences form, I can’t lift my eyes from my toes as I creep along.

Joyriders had a long gestation. Sometimes I felt bitter and frustrated—at the extremely limited market opportunities for story collections, for instance, which made it more difficult to celebrate others’ successes in what felt like a zero-sum environment; or at the broader culture and the huge mess it’s made out of so many things, including the question of what narrative content and forms to value—and those feelings, that need to publish, had a way of leaching some of the pleasure from my daily writing in a way I’m sure delayed my progress.

In the end, bringing Joyriders to fruition required not only a stroke of good fortune—a contest win and the support of a wonderful team of folks at the University of Massachusetts Press—it also, before that, required me to get over myself. The better I got at recognizing “I have to publish a book” for the egotistical hang-up it was (“I have to publish a book”), the more endurance I had for the stony climb any story writer—particularly one without a novel to offer as ransom for the collection—must make toward book publication.

INTERVIEWER

What feelings do you hope readers take away with them when they walk away from your book? What do you hope they’re thinking about when they’ve finished reading?

SCHUTZ

My sincerest hope for Joyriders is that the collection finds its particular community of readers who feel the care that went into these stories and for whom these stories feel like bespoke creations, tailored to their needs. I hope these readers feel, as I was delighted to hear you say above, seen, and that they’ll be attuned to the light that shines through the work. These are, in a sense, dark stories. There’s plenty of loneliness, heartbreak, and hurt to go around. But the characters in the collection tend to be people for whom this darkness is not an emergency but a condition. It is chronic, perhaps irreversible. They will have to learn to live with it. And—here’s the light—they do. They find ways.

INTERVIEWER

Which authors do you admire, take inspiration from? And what media (books or otherwise) served as a guide for you throughout the process of writing the stories in this collection?

SCHUTZ

There are numerous authors whose short stories live with me. I return to them endlessly, rereading, learning; their stories are inexhaustible. For brevity’s sake, I’ll confine my response to the ranks of the living and name Deborah Eisenberg, Elizabeth Tallent, Edward P. Jones, Tessa Hadley, Louise Erdrich, Jhumpa Lahiri, Valerie Trueblood, Elizabeth McCracken, Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum, and Joy Williams, among others. I could go on!

Speaking of Valerie Trueblood, her essay “What’s the Story? Aspects of the Form,” originally published in the American Poetry Review, is a magnificent explication and defense of the story as form and practice, one I’ve drawn guidance and inspiration from.

I also recommend Lynda Barry’s What It Is to any writer or to anyone interested in imagination and creativity. If you’re unfamiliar with Barry and her work, prepare to be surprised and delighted. And if you are already familiar with her, you know exactly what I’m talking about.